Updated: Here’s the recording of the webinar on comics and literacy held on 10 September. This post introduces some of the ideas and resources discussed.

Comics are often misunderstood. Many people, when they think of them at all, think of them as being the preserve of superheroes and three panel gag strips in the newspaper. Comics embrace works of all genres and they are increasingly finding a place in classrooms around the world.

A commonly used definition of comics is “sequential art.” Images, when viewed in order, give a sense of the passage of time.

Image source: http://scottmccloud.com/1-webcomics/carl/3a/02.html

This simple two-panel comic from Scott McCloud, the author of Understanding Comics, demonstrates this point. By “reading” the placement of these images as a time sequence, we build a narrative.

The art form of comics imposes no boundaries on genre, content, or indeed artistic merit. Art Spiegelman’s Maus, telling the story of his Holocaust survivor father, was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. Reading comics is an engaging experience that embraces traditional literacy skills, but also brings other skills into play as well.

Literacy skills

Most comics have words, in the form of speech, captions, or both. These written elements become uniquely engaging through their embedding in the comics medium. Many of the core concepts of literacy learning can be explicitly addressed. Sequencing and ordering of ideas is at the very heart of comics, and inference and deduction from context are also well supported by the inclusion of visual imagery. This additional visual support provides another way in to a story, and can provide an often much-needed boost to visual learners.

The use of comics in literacy teaching is finding increasing support in academic circles, as these studies show:

Comics Are Key to Promoting Literacy in Boys, Study Says

For Improving Early Literacy, Reading Comics Is No Child’s Play

Visual Literacy

Comics not only have to be read as literary texts, they also have to be read as visual texts. The artistic choices made in producing a comic shape the experience of the comic. To appreciate a comic fully requires an understanding of the elements and principles of visual design. These elements provide a common vocabulary to talk about images that can be used across the curriculum. This allows students to think about the composition of an image in the same way they consider the composition of a written text. This idea can be expanded by considering individual panels of a comic like shots in a movie. What is visible in the shot? How is it framed? Why were these choices made?

Comics literacy

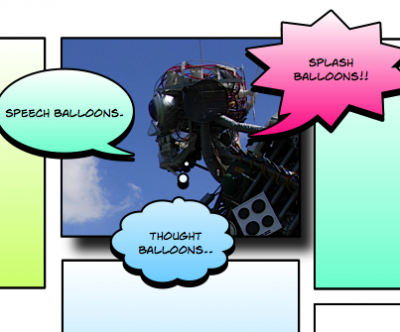

Comics are constructed in a particular way, and they use their own grammar and syntax. Each image in a comic is called a “panel”, and the space separating them is known as the “gutter”. Speech is enclosed in “balloons” and internal dialogue is often placed in “thought bubbles”. Panels are read in the same direction as usual reading order, which can often come as a surprise to first-time readers of Japanese comics!

Most of us are so familiar with reading comics that these procedures become transparent, but they are learned skills, and a vital part of reading comics.

Tools and resources

Given the place comics can have in class, here are some online tools and resources to help you and your students make their own:

Comic Life – one of the most popular comics makers, which is now bundled with EduStar for use in public schools. A simple drag and drop interface allows you to create comics with your own images.

ToonDoo – free online comic creator. Use images from the site, share your creations, and view comics made by others

A great site for news and reviews about comics is No Flying, No Tights, which as the name suggests, looks well beyond the usual superhero fare.