An important article was published in last week’s Age newspaper on the wonderful teacher librarians in our schools. Well done to all involved to highlight the issues schools are facing and to outline what our job really does involve.

Tag Archives: The Age

The Wheeler Centre: Books, Writing, Ideas

Two recent articles published in The Age highlighted Melbourne’s forthcoming Wheeler Centre: Books, Writing, Ideas.

Wheelers help turn new page at centre

JASON STEGER

November 27, 2009

WHEN Tony and Maureen Wheeler created their travel-book company at a kitchen table in 1972, they had no idea Lonely Planet would become one of the great Australian entrepreneurial success stories.

They certainly couldn’t have known that hundreds of journeys later it would lead to the centrepiece of Melbourne’s successful bid to become a UNESCO City of Literature being named after them.

But yesterday there was a new title page in the story of the Centre for Books, Writing and Ideas when it was renamed the Wheeler Centre: Books, Writing, Ideas.

The Wheelers, who sold 75 per cent of Lonely Planet to BBC Worldwide two years ago for about $200 million, have also made a substantial endowment to the centre, the income from which will be used to help fund the program of events when the centre opens next year.

The Wheelers have a philanthropic foundation, Planet Wheeler, that operates in the areas of child and maternal welfare, education and health care in South-East Asia and Africa.

Maureen Wheeler said when the idea of contributing to the centre was raised they decided it was a great way to give something back to Melbourne. ”We liked the idea immediately because it fitted in so much with the things we’re interested in. There isn’t anything like it in Australia and I love the fact that it’s in Melbourne.”

The Wheelers would not say how much their endowment was worth.

”When I compare it with what we started with, it’s a lot of money,” Mr Wheeler said. And Mrs Wheeler said, ”it was more than adequate”.

Centre director Chrissy Sharp said the substantial amount was a fantastic boon that eased the planning of events.

The centre also announced that its launch event would be held on February 13 – the anniversary of the Federal Government’s apology to the stolen generations – and would feature 12 writers telling stories that had been handed down to them through their families.

Among those taking part are David Malouf, Paul Kelly, Chloe Hooper, Alexis Wright, Christos Tsiolkas and Alex Miller. Ms Sharp said the centre’s full program would be unveiled in January.

The centre is based in a wing of the State Library of Victoria and, in addition to staging events, will provide a home for organisations such as the Melbourne Writers Festival, the Victorian Writers’ Centre and the Australian Poetry Centre.

Feisty, fabulous and full of ideas

Andrew Stephens

November 28, 2009

WHEN she was in her 20s, Chrissy Sharp strode into the Sydney offices of the then revered ABC documentary program Chequerboard and told them she wanted to work there. She had big ideas. ”I said, ‘I know I could work here: please give me a job.’ ” Sharp, who grew up in Canberra, had seen the indigenous tent embassy at Parliament House and she was in a lather to do something on it. Chequerboard, which tackled such thorny issues, took a risk and hired her as a researcher.

It was a lucky break – but then, she had been pushing for a while.

”There I was,” she says, ”at uni in Canberra, and I felt so guilty that I could be so aware of American civil rights but had never really, really, understood the plight of Aborigines. I thought, I’ve got to do something. I beleaguered Four Corners; but I was never a journalist, I wasn’t going to get a job on Four Corners – I used to get these responses saying, ‘Please apply to the typing pool.’ ” She pauses. ”And I couldn’t type.” So she went to Sydney for the old foot-in-door at Chequerboard.

These days, they come to her.

Here in her office in a wing of the State Library of Victoria – which houses the much-anticipated Wheeler Centre for Books, Writing, Ideas, where Sharp is inaugural director – she whips open a window to let the noise in. Clearly, she loves buzz and the flurry of creativity and – yes – the inevitable panic that her big new job attracts. So, windows open, that same sort of frenetic activity – the burble of trams, pedestrians and lunchtime conversations on the lawns below – filters up into her room. She thrives on it.

Chrissy Sharp, her husband, Michael Lynch, explains, is a truly formidable person. ”Woe betide anyone who gets in her way!” he laughs, uproariously. Not because she’s scary but because she’s full of warm, infectious energy; she gets things moving and she inspires loyalty. She’s immediately, immensely likeable. And very clever.

These two people have been described, rather lamely, as a ”power couple”, but there’s much more complexity and panache to it than that. You get the feeling – both of them have fantastic laughs, full of character – that they have enormous fun together when they meet up between the demanding tasks of their busy professional lives. There is, it seems, an authenticity of enjoyment about what they do and why they do it.

Last June, they arrived in Melbourne after about seven years in London, where Lynch was horrendously busy as chief executive of London arts hub the Southbank Centre; he had become one of England’s most admired and sparky arts administrators, overseeing the $260 million refurbishment of Royal Festival Hall. Sharp, who had previously been general manager of the Sydney Festival, had – of course – taken on a risky business there herself: trying to wrench ailing dance theatre Sadler’s Wells out of deep doldrums. She did more than that. By the time she left, it was the city’s pre-eminent dance outfit, with five successive surpluses and a quarter more attendees.

So it is hard to believe it when she reveals that, once upon a time, she ran a flower shop.

”It was such a long time ago, when I was a farmer’s wife,” she laughs. She had two sons in that marriage (she now has a stepdaughter, too), and a desire to open a flower shop in the NSW town near where they lived. ”It was very hard work. It meant twice a week driving down to the flower markets in Sydney and getting back by the time the shop opened. It was a lousy way to make money – but I was young. And very energetic.”

What’s changed? Now she is in full, energetic swing as director of the Wheeler Centre, her first job doing a start-up, from the ground up, with a small staff and – despite the Books and Writing bit in the centre’s title – a particularly deep interest in Ideas. Among the first people on her year-round program of events – it will be a festival that never stops – are ethicist/philosopher Peter Singer, US foreign affairs journalist Mark Danner and a top-notch panel teasing out the minefield of media ethics, led by former Ageeditor Michael Gawenda.

”The importance of cultural nourishment, whether it be through books or dance or music, is just vital, I think, to society, ” says Sharp, who has never lived in Melbourne but is agog at the depth of intellectual life she has discovered in just a few months. She wants the centre – named after Lonely Planet founders and philanthropists Tony and Maureen Wheeler, who have made a generous endowment – to be the sort of place where writers and thinkers talk about ideas, not just their own books. As Maureen Wheeler told one interviewer at this week’s announcement of the centre’s name, there were tough questions to ask before investing. But the Wheelers were very impressed with Sharp and with the concrete ideas behind it – it wasn’t, said Wheeler, the sort of ”arty” thing that says, ”Ideas, what are ideas?”

Indeed, Sharp is very pragmatic on this, noting that the recent economic downturn has provoked a lot of thinking about fundamental ethics and directions, a questioning of assumptions about endless growth and wealth. ”People from everywhere in society are interested in ideas,” she says. ”We want to take it into the town square, if you like, and bring some of our own fantastic thinkers who are in campuses around Melbourne or Australia, into a different kind of forum: where their ideas are accessible, where people get a familiarity, with not expecting it to be too high-brow, too rarefied or too boring. It’s got to be entertaining.”

The centre, housing the Melbourne Writers Festival, Victorian Writers Centre, Australian Poetry Centre and other literary organisations, was established after Melbourne won its bid for UNESCO City of Literature. It has a large performance space and workshop areas, where Sharp is planning forums that will spark debate.

”It seems I have yet to meet a person in Melbourne, especially women, who don’t belong to a book club,” she says. ”It – this city – seems to just absorb the idea of writing and the importance of books. It’s kind of a given, it seems to me. Everyone – my hairdresser! The guy who was painting the door the other day: I was sitting here talking to the chairman … and I mentioned [Orhan] Pamuk. [Later] the painter said, ‘I’m sorry, but I heard you talk about Pamuk.’ I asked him if he was Turkish; no, it was just that he and his wife lovePamuk. I love that! I was so impressed.”

She’s finding this all through Melbourne. ”It’s not just the job I’m doing: people do talk about the books they’re reading, or the ideas that they’d like to hear – they’re incredibly well informed. It is sucha writer’s place. Going out for lunch, there’s always some sort of fervent discussion about something to do with writing or books – it is a very intellectual city. Michael and I used to laugh about the fact that you’d come down from Sydney and you’d sit down to lunch and there’d be some intense” – she almost yells the word – ”argument going on. That is very Melbourne.”

There were some sour musings when Sharp’s appointment was announced last February: she, after all, is an outsider whose connection with the place had not extended much beyond holidays to aunts and grandparents here when she was a girl. Equally, though, she hadn’t set foot in Sydney until she was 16. But outsiders – she faced the same pursed lips when she took on Sadler’s Wells in London – often have the clearest view of what’s going on in a place and the sort of unsentimental temerity to get things done. She proved that at Sadler’s Wells as general manager alongside artistic director Alistair Spalding, and she looks like doing so here with her winning combination of financial and staff management, plus artistic, creative flair.

Lynch is droll about her dynamism. ”Much too much energy for my liking,” he says. ”I think she approaches life very full-on – they are lucky to have someone with the attention to detail and the energy that she brings to it. That’s going to stand the organisation in quite good stead. And she does command hugely loyal groups of people working with her. I’m not sure I would have quite had the energy at my flagging point in life to do it, but she seems to have driven herself day and night to make sure they could realise the potential of the idea.”

Lynch says he and Sharp worked amazingly hard in London. ”I dragged her to England to back me up, but she didn’t want to play dutiful wife entirely, so she took on Sadler’s Wells. I thought it was my turn to be a little more supportive and a little less demanding, with her being in this new role. Being in a new town, she has sent me out to find the house and do those sorts of things.”

While she has never worked with her husband, who has joined the ABC board, the two, he says, had one notoriously amusing conflict of interests some years ago when she was representing actors in the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance and he was running the Sydney Theatre Company.

”This was sort of indicative of her hide,” he confides, laughing. ”The actors’ union were taking industrial action against all of the major theatre companies, so she led a picket line outside one of our opening nights in Sydney. I was standing inside and she blandished kisses at me and said, ‘Come out and talk to me!’ I had to say, ‘No darling, I never cross picket lines. Even for my dear wife.’ She’s always been a feisty woman in that respect.”

SHARP grew up in a family where books were at the centre of things and she says that anyone who knows her isn’t surprised she has ended up heading a centre concerned with writing and ideas.

”My intellectual life for most of my childhood was books and music, inevitably,” she says. Her father, Ted Hannan, was a highly acclaimed professor of statistics at ANU, a man described by one biographer as ”outspoken, frequently irreverent” but ”transparently honest”.

”And my mother just loved music. My father’s interests, apart from mathematics, were very much history, biography and poetry, and it was my mother who introduced me to the whole canon of 20th-century American writers, in particular, and of Australian writers. It was very much a household that talked about books all the time. Then I went to university, started doing literature and history and ended up doing honours in history with Manning Clark, who’s very much a literary person. So books and literature and history were my forming influences.”

But she says that while it was her dream at university to become a writer, she has since found she is ” the one person who doesn’t have a novel in me.

”I realised in my early 30s, no I don’t think I have a novel to give the world, not of any great interest or importance. I am lucky having realised that at a reasonably early age – to have [since] been in positions where I can enable arts has been incredibly satisfying. I have been around enough to know that the people who do the hard work are the creators. They’re the ones that I hold on a pedestal.”

Lynch, it seems, might hold her there, though. ”Formidably smart,” he says. ”She scared me for many years on that front. She’s always been the one who’s read the books and had the brain and she’s always been a formidable person to argue, discuss or engage with. And I think she’s really thrilled [with her job]: books have always been a passion but she’s always been very good on ideas.” And at putting them into action.

A very exciting time for those of us passionate about books, writing and ideas.

Lost in cyberspace

This lengthy but thought provoking article appeared in The Sunday Age on Sunday 15 November. It asks the question that if “possessions define us… what does it say about our identity when iPods replace CD racks and Kindles take the place of bookshelves?”

How many of us have perused the CD collections and bookshelves of friends and lovers to help us form our opinions of them?

PETER MUNRO

November 15, 2009

A YEAR or so ago, Professor Bob Cummins, convener of the Australian Centre on Quality of Life, emptied his shelves of books and left them on a table where staff and students at Deakin University give away unwanted stuff, like promotional CDs and old pieces of fruit.

It was liberating, he says. Utterly practical, too, given almost every piece of information he will ever need is available in compact electronic form. But he glances at his bare wooden shelves now and pauses. ”I feel like I have lost a social marker,” he says, finally. ”The fact is that I just never read those books and was never going to read them again – they were just academic props. But maybe they filled a function as that – as a prop for who Cummins is … probably shouldn’t have done it.”

Entering his office, you search for clues to reveal his likes and dislikes, fascinations and expertise. ”I guess walking into an academic’s office and finding a wall of earnest books is quite consoling; it means at face value you look like the real deal. Someone sitting in their office with bare shelves – how odd, what’s wrong with them?”

Perhaps a giant wall poster of Albert Einstein might suffice, he says, laughing. Anything to fill the void left as visual markers disappear behind blank computer screens.

Possessions help define us, brand us, but what happens when they start to hide away in boxes in top cupboards – CD stacks supplanted by iPod docks, film collections by downloads, libraries by wireless reading devices. Perhaps it’s part of a broader disconnect from society. As the world grows more intrusive, we retreat.

An article in Vanity Fairin August called this trend ”The Vanishing”. In mock-horror tones, the glossy mag moaned how homogenous e-books and iPods had stopped culture snobs showing off their superior tastes in literature and music to the masses. Equally, it was becoming impossible to spy on other people’s tastes and make judgments about them.

Sitting on a New York subway, writer James Wolcott watched a woman hold up a Kindle – Amazon’s wireless electronic reader, which became available to Australian readers this month – at an angle to catch the light. ”Unless you were an elf camped on her shoulder, what she was reading was hoarded from view, an anonymous block of pixels on a screen, making it impossible to identify its content and to surmise the state of her inner being, erotic proclivities, and intellectual calibre.”

Books ”help brand our identities”, he wrote. So what might become of us as such branding vanishes? Book jacket design might become a lost art, like album-cover art. The average coffee table book may not survive. Selected titles might be showcased in wall-mounted frames, with a small, built-in ledge, like a stage. Imagine every home displaying Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father above otherwise clean, white bookshelves.

Beyond books, technology means we have to squint or turn our heads sharply, to read the small print on the sides of DVD cases. Music is now ”residing in our heads rather than resounding off the walls”, as speaker docks have replaced CD collections. Some bloggers have resorted to posting shuffle lists of their iPods online to advertise their eclectic tastes. Parties are reportedly held at which young hosts now hook up digital frames to their iPods, simply so guests can watch album cover images for whatever tunes are playing.

One particular passage in Vanity Fair, quoted in turn from The New York Times, resonated: ”After two decades of defining ourselves in terms of our possessions, we now need to figure out who we would be without them.”

Two years ago, I packed my meagre music library of about 200 CDs inside a cardboard box, inside a bedroom cupboard I need a chair to reach. The heavy wooden CD tower vanished from the front yard in the next hard waste collection. In its place, sitting in a speaker dock in my living room, is an anonymous iPod that can store about 20,000 songs – each of them nicely arranged by artist/album/genre.

It’s neat and clean and compact, if not a little lonely sitting there atop the bookshelf. I wonder if my small library of books might one day disappear the same way, subsumed by a single digital device that I can take on holidays and read on the beach without the breeze ruffling the electronic pages. But what to do with all those bare shelves?

Futurist Mark Pesce packed about 2000 books in a storage unit in California six years ago before moving to Australia. He visited them last year in an attempt to winnow away about half the titles – but it’s hard graft. ”In a way that no other possession I own is me, they’re me, they’re absolutely me,” he says.

And yet, he reckons weighty textbooks, which are expensive to print for a niche market, may one day be sucked holus-bolus into digital reading devices. Reading for pleasure, whether handsome literary classics or those airport books hidden at the back of the bookshelf, will be the last thing to go. ”The thing that has scared me the most is, as an intellectual, I always like going into someone else’s house who is an intellectual to see what books they have. I find it extremely satisfying and exciting to look through someone else’s library,” he says.

”But I strongly suspect they will reappear in some other form. Already, some web-based services, such as Safari, are like a library where you can indicate what books you read. They’re like a web-based bookshelf, so before you go to see somebody, you drop by their electronic bookshelf and see what they’re reading.”

A Twitterer he follows recently declared how much he enjoyed listening to the rather earnest West London folk band Mumford and Sons. Once, Pesce might have had to rifle through a CD collection to make such a discovery. Now, many people are more inclined to reveal themselves through digital pointers rather than actual physical objects.

It’s different, sure, but who says it’s better? There are some obvious pitfalls to relying largely on the self-selections of others. On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog. But nor do they know you’re lying when you pretend to have read Proust. A university peer once claimed he had finished Ulyssesand thought it ”not a bad read”. I wanted to punch him in the jaw. Now, he can list his most memorable titles on booktagger.com.au, and annoy so many more people all at once.

Pesce says there is so much clutter online that something has to give. ”I read a Tech Lunch piece by a music reviewer who realised his 14-year-old son had been exposed to more music by that age than this older man had been in his entire life,” he says.

”This 14-year-old had never lived in an age where media has never been instantly available at the click of a button. Now we have an age of such hyper-abundance of media that, in fact, there is no place we can put it all. So much is coming from everywhere that things need to vanish.”

Here’s a neat game: next time you see someone wearing headphones on the train or walking down the street, stop them and ask what they’re listening to. You may need to nudge them to get their attention.

I tap Shane Cameron, 36, project manager for a smallgoods company, on the shoulder as he stands on crutches at Southern Cross Station, waiting for a train to North Melbourne. He’s been forced to catch the train since knee surgery – the downside to years of indoor soccer and taekwondo – and passes the time listening to Texan alternative rockers Sparta on a white iPod. ”It relieves the boredom,” he says. ”I always have something to keep myself occupied.”

On a separate train to Flinders Street Station, Gerard Richardson, 20, is listening to Canadian singer-songwriter Feist, while reading The Making of Julia Gillard. Small-business owner Anna Parente, 62, alights at South Yarra Station with a portable radio tuned to 3AW. ”I’ve had three train cancellations this morning. I’m furious. This takes my mind off things,” she says.

Massage student Jess Keighran, 21, is travelling to Richmond from Essendon, and leaves one earphone in while we speak. ”I usually read and listen at the same time, so you don’t have to listen to other people’s boring conversations. I just zone out, forget about what’s around me,” she says. What are you listening to now? ”I’m listening to nothing, the music just stopped.”

We plug in and plug out, often as soon as we walk beyond our front door. The headphones go on, we tap away at text messages or hunch over mobile phone screens on the train, playing solo computer games or watching the latest episode of our favourite TV shows. It’s another form of vanishing, really. Another way we disappear behind mobile technology, disconnecting from the inane bluster and bustle about us. Morning peak hour is like being stuck inside a mobile phone dead zone, with only the tinny bleed of noise from your neighbour’s overloud MP3 as company. It doesn’t matter that no one’s talking to each other, because no one’s listening any more.

Well, almost no one. Sound designer David Franzke spent 18 months riding Melbourne trains to record conversations for use in Anna Tregloan’s play, The Dictionary of Imaginary Places, which premiered at last month’s Melbourne International Arts Festival. The sound of silence made his work frustrating, he says now, as we trundle along on a city-bound train from North Melbourne at 9am.

We are close enough to touch our fellow passengers, their hands busy checking text messages or sending emails, their ears piped with blather. I’m conscious Franzke, scruffy and curious amid so many suits, is the only one talking. ”I don’t think a lot of people get to do what they want to do with their lives. They end up taking a gig where they have to pull on a suit and go to work every day, and I don’t think it’s very much fun and I think they do shut down,” he says.

”You don’t hear as much now as you once did. You watch a group of kids who are travelling to school together and, let’s say there’s seven of them, at least three are going to have earbuds in their ears. They hit each other to get their attention.

”You see a lot of girls split their earphones to have one each, so they actually are in each other’s worlds for a little while. But it’s devolution not evolution. We’re actually losing the ability to communicate.”

Deakin University’s Bob Cummins – he of the empty bookshelves – says such disconnection is symptomatic of an age when people increasingly live alone. Paradoxically, at a time when it is possible to touch more people than ever before online, we position ourselves as islands from each other. ”People are retreating into themselves even further and taking themselves away from the bothersome interaction of other people,” he says.

”You can only do it in the anonymity of a large city. But people might want to do it because they are so overloaded with other information, or overloaded from too much social contact from Facebook – I mean, how much can you deal with?”

But Jenny Lewis, author of new book Connecting and Co-operating, instead sees Facebook and Twitter as opening opportunities for new, far-flung social interactions. ”To say we don’t know everybody who lives in our street and we don’t all go out for dinner, doesn’t say we have no friends. We have changed away from very local versions of connectedness to these other, maybe even virtual, communities,” she says.

We still use social markers to reveal our preferences and dislikes to others, but in less tangible ways, she argues. ”I see people comparing libraries on iPods and iPhone apps. It is not so easily accessible to look at things on bookshelves but I think people still swap and share their connections, just in different ways.

”Some people use their iPod defensively, to block out inane talk, but you wonder whether it is very different from how it used to be. It is not as if people used to strike up conversations that often before. We’re just so busy and time poor that we often feel too stressed and don’t feel we have time to do those basic things. So the moments we do get, we want just to ourselves.”

One train conversation detailed in The Dictionary of Imaginary Placesinvolves a girl who says she wants to quit Facebook because she feels too exposed. ”I don’t want to be found, that’s why I moved away,” she says. ”I actually hate it when I go in there cause there is 1001 messages going, ‘So and so has requested a friendship. So and so has changed their mood.’ Some people I might have gone to high school with; I might have sat next to on the train and I wouldn’t know.”

Her words ring in my ears as I stand on a quiet train, stuck in the interminable circle of hell that is the City Loop, and notice a man in the carriage reading Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

An older man in a dark blue suit sits with his white earphones in and his eyes closed, a beatific smile on his dial. And I wish I were in his world, if only to the next station.

I recently culled the vast majority of my CD collection as I was sick of dusting them and I never listened to them outside of the iPod. Books will prove different for many teacher librarians I believe, me included.

Google Wave

So we all know that Google has practically taken over the world. Some of their applications like maps and earth are fabulous and others such as Sidewiki and Google Apps for Schools have been quite controversial. We’ve all been hearing about Google Wave for months now and how it is going to revolutionise communication.

A little over a month ago Google sent out 100,000 invitations for people to trial Wave, but there is no public release date as yet. However, it’s time to get (almost) ready for one of the biggest Web 2.0 launches in history.

Some information from “About Google Wave” from their website:

About Google Wave

Google Wave is an online tool for real-time communication and collaboration. A wave can be both a conversation and a document where people can discuss and work together using richly formatted text, photos, videos, maps, and more.

What is a wave?

A wave is equal parts conversation and document. People can communicate and work together with richly formatted text, photos, videos, maps, and more.

A wave is shared. Any participant can reply anywhere in the message, edit the content and add participants at any point in the process. Then playback lets anyone rewind the wave to see who said what and when.

A wave is live. With live transmission as you type, participants on a wave can have faster conversations, see edits and interact with extensions in real-time.

This following video is an abridged version of the really long one (one hour and twenty minutes out of your busy life, is probably way too much), so this ten minute video should answer some of your questions about Google Wave.

Another useful source of information on Google Wave comes from the current Age Green Guide:

Next wave may sweep all aside

Google’s email and messaging platform could change the web forever, writes Adam Turner.

RED pill in hand, Google is offering to show us how deep the rabbit hole goes with Google Wave.

Every now and then, someone develops a new way of thinking about an old problem. Email has become so bogged down with spam and other problems that for many people it’s all but useless. Attempts to make email more secure have struggled to make headway because the email system was never designed with such things in mind.

The boffins at Google — well, actually Lars and Jens Rasmussen, who brought us Google Maps — asked “What would email look like if we set out to invent it today?” Their answer is Google Wave, a free service that has the potential to change the face of the internet.

Like The Matrix, Google Wave is Australian-made, with the Sydney-based Rasmussen brothers spending much of their time at the new Googleplex near Darling Harbour. Also like The Matrix, it’s hard to explain exactly what Google Wave is. It’s been described as “Twitter on crack” or “Friendfeed with benefits”, while others see it as “Lotus Notes on steroids”.

Everyone sees Google Wave as something different because they’re bringing their own preconceptions to it — just as the first cars were known as “horseless carriages”.

In simple terms, Google Wave is like a cross between email, instant messaging and wikis [a wiki is a webpage that allows anyone to make changes].

Google Wave is still in the early development stages and Google isn’t even calling it a “beta” yet. After offering a “preview” to a few thousand developers, Google extended Google Wave invites to 100,000 early adopters. As with Google’s email service, Gmail, Google Wave invites will remain a precious commodity for a while.

Similar to Gmail, Google Wave runs inside a web browser such as Internet Explorer or Firefox. The interface looks similar to Gmail and eventually Google may combine them in one service. Creating a new message, or “Wave”, is simple enough: just click New Wave and a fresh window opens on the right of the screen. You can start typing straight away, with basic formatting options as well as the ability to attach files. You can also insert links to other Waves, content from webpages, maps, links to other services such as Twitter and tiny applications such as a Yes/No/Maybe poll.

Sharing a Wave is simple; you can drag them across from your address book or search for them. Once you add someone to a Wave, it will appear in their Google Wave inbox. Now they’ll be able to see what you’re typing, letter by letter, marked by an icon with your username in it.

You can add as many people to a Wave as you want and even make it public so anyone with a Google Wave account can see it and contribute.

Each person can make comments, with a single comment known as a “Blip”. They can can also reply to and edit comments made by other people. Eventually you should have the option to restrict how people can edit your comments.

You can’t always read a Wave chronologically from top to bottom because anyone can interject at any point to make a comment and start a new conversation (known as a “Wavelet”).

Thankfully, you can replay a Wave — comment by comment — to see how it developed.

At first, the real-time nature of Google Wave makes it tempting to use it like instant messaging but you find yourself talking over each other. It seems better suited to real-time collaboration, with different people editing different parts of a Wave similar to a Wikipedia entry. It’s perfect for holding asynchronous conversations that run over days, similar to online forums. Anyone who has used clunky and expensive business-grade collaboration and project management tools will see the potential for Google Wave.

Of course, these ideas are falling for the trap of trying to fit Google Wave into concepts we’re familiar with. Developers have been busy creating new applications that will run inside Google Wave. This will allow it to be a platform on which other services are built, in the vein of Facebook. It has the potential to replace email, instant messaging, forums, wikis, blogs and even traditional publishing outlets — combining them into something we can only begin to imagine. In other words, Google is building Web 3.0 inside Google Wave.

Actually, that’s not quite true. Rather than building Google Wave and delivering a polished final product, Google has handed the online community a rough first draft, along with the tools to create Web 3.0.

Rather than saying “build it and they will come”, Google is saying “give them a clean slate and they’ll build it themselves”.

As such, Google Wave is an amazing place right now, like a new nation that has sprung forth. Not only are these new digital citizens building cities, they’re deciding how their society is going to function — in preparation for a population explosion. The limited membership means Google Wave is still a bit of a utopian playground free from spammers and griefers — for now.

To wander around in Google Wave feels like standing next to Romulus and Remus, overlooking the seven hills of Rome, or watching over Thomas Jefferson’s shoulder as he writes the US Constitution. Only time will tell what becomes of it.

It seems that Google Wave will have applications for library and school teams as well as students who should (apart from time zone differences) now be truly able to fully collaborate with counterparts virtually anywhere in the world.

Please note that as at 5 August 2010, Google Wave has been discontinued. Read the article from Mashable here.

Stemming the tide of cyber bullying

This article was published in today’s Age newspaper and the results of the summit seem to be a step in the right direction regarding the problem of cyber bullying.

Stemming the tide of cyber bullying

FARRAH TOMAZIN

October 13, 2009

Korumburra Secondary College classmates William Crawford and Courtney Graue were among 240 students at the state’s first cyber bullying summit. Photo: Pat Scala

A year ago, Korumburra Secondary College student Courtney Graue became the victim of a sustained campaign of cyber bullying. What started off as schoolyard taunts and social exclusion soon transcended into the online world: derogatory messages posted on her MySpace page, claims that she didn’t have any female friends, even comments about her appearance.

”I guess girls can get jealous of different things and one girl in particular would tell me I was ugly and that I only hung out with guys because no girls would want to talk to me,” said the year 10 student.

”In the end I talked to my teachers, and even to my parents, and they sorted it out. I got over it eventually, but at the time I got fairly upset by it all, and it certainly does impact your life.”

Courtney’s story is emblematic of a much broader trend: the latest research from Edith Cowan University suggests that on any given day, about 100,000 Australian children will be bullied at school. And between 10-15 per cent are cyber bullied through social networking websites, instant online messaging, mobile phones or other forms of digital technology.

Yesterday, Courtney and classmates William Crawford and Daniel Whittingham were among 240 year 10 students who took part in the state’s first cyber bullying summit.

The conference, involving 60 public and private schools, was convened by the Brumby Government after it became so concerned by the extent of cyber bullying that it decided to seek the advice of young people on the best ways to tackle it.

While the Government has tried to crack down on the problem by updating bullying guidelines and blocking access to video-sharing websites such as YouTube and MySpace through a filter system, experts agree that past policies have not done enough.

Appearing at the conference yesterday, Premier John Brumby admitted that the ever-changing nature of digital technology had serious consequences.

”The openness and ease of online communication comes with a downside,” he said.

The summit comes only months after the death of 14-year-old Geelong schoolgirl Chanelle Rae who, according to her mother Karen, took her own life after reading something posted about her on the internet.

Edith Cowan researcher Donna Cross said it was hard to quantify how many youth suicides had been caused by cyber bullying, but there was little doubt it was a contributing factor in some cases.

The message

Now screening: a digital book for you

In an ironic twist, Saturday’s Age published two stories about e-books. One by author Carmel Bird (see previous post) who states that the intimacy of turning the pages of a book can never be replaced. The second by Jane Sullivan explains how readers of The Age can access a new and exclusive digital story:

Now screening: a digital book for you

JANE SULLIVAN

October 3, 2009

“NOBODY is going to sit down and read a book on a twitchy little screen,” US writer Annie Proulx said in 1994. “Ever.”

What a difference 15 years make. Today, millions read books on a variety of “twitchy little screens”: laptops, e-books, iPods or iPhones. And from October 12, Age readers will be able to read a serialised story on their mobile phones.

In the tradition of Charles Dickens, who launched his novels in serial form, Melbourne writer Marieke Hardy has created a 20-episode story, to be sent out to mobiles over four weeks.

”It will be quite riveting,” promises The Age’seditor-in-chief, Paul Ramadge. “Marieke is a wonderfully talented and immediately engaging writer.” The idea is to test the story’s reception, get reader feedback and develop the potential to talk to Age readers “in multiple ways”.

It’s probable that this is Australia’s first sizeable fiction written for the mobile phone. But in Japan, millions of readers are devouring novels on their phones, often when commuting to work or school. They download the novels – usually racy romances – and read them in 70-word instalments.

As many as 86 per cent of high school girls read these phone stories, and the novels subsequently turned into print form have raced to the top of bestseller lists.

In other countries, alternatives to the traditional book are catching on more slowly. But Nick Cave wrote the first chapter of his novel, The Death of Bunny Munro, on his iPhone, and the book is available as an iPhone application.

Hundreds of other titles are being downloaded on to e-book readers such as Kindle or Echo Reader, or smartphones such as iPhone or iPod touch, either free or for a fraction of the price of a print book.

Melbourne mobile media theorist Paul Green does not see these alternatives taking over from print. “The novel is going to be pretty awkward to read on the small screen,” he says. “But there will be a place for the audio book, and a trend towards reading and writing short books with short chapters on these devices, as their screens get bigger.”

Sydney writer Richard Watson, author of Future Files, thinks the publishing world is about to undergo a seismic shock. Books as we know them will exist beside a host of new alternatives.

The creation of a book may not include an agent or a publisher: instead, authors will self-publish using software and online services such as Blurb, and search out niche markets. As well as downloading books, readers will print them through automated publishing machines, or buy e-books in 99-cent instalments.

It’s enough to make you want to get away from it all and curl up with a book.

Details of how to register for The Age mobile phone story will be announced next week.

It will be interesting to gauge the response to the digital story.

The intimacy of turning pages

This lovely article by author Carmel Bird appeared in Saturday’s Age:

CARMEL BIRD

October 3, 2009

IN A photograph of the Obama family at home, taken by Annie Leibovitz in October 2004, surrounded by images of Abraham Lincoln and Muhammad Ali, there lies, all alone on a clear surface, front and centre, a slightly dog-eared copy of Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White. It’s a cosy, informal family portrait, suggesting maybe that just before it was shot one of the parents was reading the storybook to the little girls. The book, flat on the table, draws the eye, and suggests that the photographer has interrupted an intimate and blissful moment, a moment familiar to many parents and teachers.

I treasure memories of lying in my father’s arms while he read from a green-covered volume of The Wind in the Willows, a book that gradually fell to pieces from loving over-use. The books I read to my daughter have a glow and resonance in my mind and heart. Some are still in either my possession or hers, but sometimes I think of one, and if it is lost, if it is out of print, I rush to find a second-hand copy. These replacements have a special quality of their own; they are part of a treasury of reclaimed and revisited moments of intimate bliss.

I recently got a replacement copy of a picture book called Miss Jaster’s Gardenby N.M. Bodecker. This is a story about a hedgehog that becomes part of the garden to the extent that flowers grow in his prickles. A rather poignant thing about the book I got is the inscription in handwriting — “To Grayson from his loving Aunt Jeni and Uncle Brett, for Christmas 2003”. But then maybe our old copy has wound up on someone else’s nursery bookshelf. I hope so.

On the day I received Miss Jaster’s Garden in the mail, I was writing a speech to give at the launch of Glenda Millard’s gorgeous new picture book, Isabella’s Garden. And I was listening to the radio. There I heard someone speaking about the coming disappearance of books as paper objects. They will be replaced by electronic devices of various marvellous kinds. This assertion seems to be quite widespread, but was strangely at odds with my pleasure in the two picture books on my desk.

In lots of ways I am old-fashioned, but I am also pleased to use quite a bit of modern technology. I don’t deny that there are and will be ways of reading that do not rely on blocks of paper covered in black type. I read things on the web and I often enjoy the experience. But if books as books are going to disappear, what will replace those Wind in the Willows/Charlotte’s Web moments that nourish the love between adults and children, and that sow the seeds of storytelling and language?

Does it matter? I think it does. I was reading How Fiction Works by James Wood. Referring to the “cherry-coloured twist” in Beatrix Potter’s The Tailor of Gloucester, Wood says: “Reading this to my daughter for the first time in 35 years, I was instantly returned, by the talismanic activity of that cherry-coloured twist, to a memory of my mother reading it to me.” The book, the language, the melody of it all, are part of the embrace of the mother for the son, the son in turn for his daughter. The stories of Potter are not simply a collection of disembodied words, but are part of something organic and emotional that goes where electronic reading devices possibly cannot go.

And it’s not just the children’s storybooks that will disappear with the book, so will the beloved physicalities and idiosyncrasies of all books. I have a lot of books, although I could not be described as a “collector”. They line the walls of several rooms and make me feel at home. In a mild and haphazard way, I am a collector of different editions of The Great Gatsby. I love all the different cover designs. Apart from fascinating differences, each edition brings back memories of when and where I got it, when and where I read it.

There is a moment, perhaps more touching now than when it was written, when Nick encounters the owl-eyed man in Gatsby’s library. The man asserts with amazed excitement that the books on the shelves are not fakes. “Absolutely real — have pages and everything.”

So altogether it seems to me it will be a sad world if books are completely replaced by other devices delivering text and information. Who would not want to see the pages turning, to hear the voice of their father intoning: “So he scraped and scratched and scrabbled and scrooged and then he scrooged again and scrabbled and scratched and scraped.” The words are good, but my father’s voice coupled with the memory of the velvet autumn leaves on the armchair gives them a marvellous added resonance. Or if you are James Wood reading to your daughter, you can hear your mother in your own voice, possibly reading from your childhood version of the book: “Everything was finished except just one single cherry-coloured button-hole, and where that button-hole was wanting there was pinned a scrap of paper with these words — in little teeny-weeny writing — NO MORE TWIST.”

You can find the texts of Potter and Kenneth Grahame on the web, where you might have the added entertainment of pop-ups offering you lovely Russian girls or cures for blindness, but I believe that nothing can really replace your mother or father holding you in their arms while they read you the story from the dog-eared little book.

Technology and e-books have their place, but who can deny the pleasure of reading and sharing a book that you can touch?

Cyberbullying

After the tragic consequences of the recent incident in Geelong that apparently had links to cyberbullying, here are some websites that teachers and students may like to know about. Jo Robinson, from Orygen Youth Mental Health Services suggests:

- beyondblue

- headspace

- Reach Out

- MoodGYM (which uses game playing to teach good decision making and other skills).

Other resources include:

- Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800

- Lifeline 13 11 14

- SANE helpline 1800 187 263

The Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development has a Cybersafe Classroom page while the Australian Media and Communications Authority has developed cyber(smart:) resources for students (of all ages), parents, schools and libraries. ACMA also offers Internet Safety Presentations.

There was also an article in Saturday’s Age that might be of interest to teachers and parents.

Once upon a digital time

A very interesting article on e-books was published in The Age on Sunday (the headline of the print version was E is for eye-pod):

Once upon a digital time

Christina Bell, of Mitcham’s Central Book Services, browses her e-reader over coffee.

Photo: Pat ScalaLiz Porter

June 21, 2009MOST evenings Mandy Brett curls up on her couch to read a new Australian novel on her Sony e-reader, an electronic device that stores up to 350 books and allows her to “turn the page” with a flick of her finger. The senior editor at local company Text Publishing, Brett, 46, switched to e-reading 18 months ago because lugging manuscripts home was giving her a sore back.

A self-described “gadget head”, she is already onto her second e-reader, having recently upgraded to a newer version of the device. If she’s stuck waiting for a friend in a cafe, she’ll whip out her iPhone and read a few pages of Let the Right One In, a novel by Swedish writer John Ajvide Lindqvist.

For Brett, the e-reader means work. When she reads for fun, she sticks to paper books. The current embryonic state of Australian e-publishing makes it easy for her to keep her dual reading lives separate. As yet, she says, there are still too few local e-books available for download. While all major Australian publishers, including Text, are preparing for digitalisation, the only locals already selling e-versions of their titles are Pan Macmillan and Allen & Unwin. The only book chain marketing them is Dymocks. And the only bookshops where would-be customers can inspect an e-reader are Dymocks’ main Sydney store and Melbourne’s Reader’s Feast.

If Brett were in the US, she could have a $US359 Kindle – a wireless e-reader launched by Amazon.com in late 2007. Without going near a computer, she could use her device to download any one of many thousands of Amazon.com titles – and pay only $9.99 for the privilege. And she would be one of a growing mainstream crowd doing so. For every 100 “hard” book copies ordered on Amazon, an additional 35 Kindle editions are now being sold.

For more than 10 years, the e-book has been hyped as the “next big thing” in world publishing – a prediction usually underpinned by dire prophecies about the imminent death of the conventional “hard” book.

Now, more than a decade since the launch of the first clunky, chunky, expensive e-readers (one of which lost its stored information when the batteries were changed), the e-book era seems finally to have dawned, at least in the US.

E-publishing was the hot conversation topic among the 1500 publishers and booksellers gathered at last month’s BookExpo America in New York. American publishing association figures for the first quarter of 2009 had just revealed that e-book sales comprised 1.6 per cent of US publishing sales – a formidable increase, given the fact that, pre-Kindle, they were languishing at about 0.2 per cent. Moreover, e-books were the only book industry sector showing any kind of sales surge amid the global financial crisis, rising 131 per cent during that period.

Sydney bookseller Jon Page was at the BookExpo and says the buzz about e-books was real, offering proof that “the reality (of e-publishing ) was starting to outpace the hype”.

But when will the e-book revolution hit Australia? For many individuals, it is already here.

Melburnian Christine Bell is working in the midst of it. The manager of the technical helpdesk at Mitcham’s Central Book Services, which supplies the readers that Dymocks and Reader’s Feast sell, she says there are two groups of e-reader buyers. Twentysomething students love them. And so do 50-somethings, who have the time to read and explore the new world of digital reading – and the money to buy one of the five different e-readers that her company supplies, at prices ranging from $569 to $1600.

Herself a keen e-book reader, Bell owns a $569 Hanlin V3, containing free out-of-copyright classics from Gutenberg.com, along with Matthew Reilly’s Seven Ancient Wonders, which she bought from the Dymocks-Pan Macmillan site. A regular on the internet e-book forum mobileread.com, she also organised a meeting of 14 e-book buffs in a CBD cafe last weekend. All brought their different e-readers, including one Kindle.

“One woman came from Sydney for it,” she says.

The e-book revolution has also arrived for 40-something Melbourne communications manager Lisa Bigelow, who was thrilled to find that her iPhone came with the Stanza book-reading application. She promptly bought a program containing 40 classic novels, including Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities.“It’s something you can read when you are waiting somewhere,” she says. “It saves carrying a book around.”

Meanwhile, the e-reading revolution has been slowly emptying the bookcase of Sydney-based accountant Charlie Perry, 31, who bought his Sony PRS-505 e-reader (the version before Mandy Brett’s PRS-700) for $450 on eBay in January last year. “That’s about half the price of buying an iRex iLiad (the e-reader Dymocks launched in December 2007),” says Perry, who happily uses his e-reader on the bus.

“I am a big reader – and I like gadgets. The e-reader weighs about 300 grams – about the same as a hardback book.” But he still reads paper books because, as with all Australian e-book fans, he is stymied by the comparative unavailability of Australian e-titles. He is also thwarted by the fact that many overseas book sites “lock out” buyers with Australian credit cards because they only have the rights to sell books in their particular territories. E-book fans, he says, share tips on “fooling” overseas sites into selling to them (by giving a US address for example), while gift vouchers allow Australians access to US sites.

His 18 months of e-reader ownership have transformed Perry’s attitude to book ownership – prompting him to give “hard” books away once he has read them.

“I’m determined this year to get my backlog of unread books down to zero, clear my bookshelf completely and move entirely over to digital reading. You come to value the experience of reading far more than you value the object. This, I suspect, is going to become a major issue for booksellers. The cost of reading a book must be cheaper than the cost of owning it – and significantly so.”

When publishers and booksellers speak of the arrival of the e-book revolution, they mean a visible, measurable and profit-making phenomenon. That phase, they agree, will probably begin in the next year or so, and will be kicked along by the launch in Australia of the Sony e-reader, expected in the next 12 months.

But opinions vary on the preconditions necessary to kick off a local e-book boom.

HarperCollins marketing director Jim Demetriou says his company has plans to offer every new title in e-book format, expanding its range to 1000 over time. But he believes e-books will only hit the mainstream when Australians get something like a Kindle. The launch of the Sony PRS-500 was the first breakthrough, he says.

“Before that, people were reading books on Palm Pilots. When Sony launched, sales doubled. But what drove sales in the US was the Kindle,” he says. “It quadrupled sales overnight.”

Others, such as Text’s Mandy Brett, or Australian Booksellers Association CEO Malcolm Neil, say lack of a sufficient breadth of “content” is the problem.

“Forget the Kindle and the Sony reader,” says Neil. “We can get hold of those. We can’t get hold of the books.”

E-publishing will remain “a world trend still waiting to happen in Australia” until all publishers, not just Pan Macmillan and Allen & Unwin, make their titles available in e-book form. According to Neil, Australian booksellers are watching overseas e-publishing growth with increasing frustration. Not because they are worried about competition with e-books, but because they want to be part of the e-publishing action.

“Our biggest concern is that if publishers hold off too long on developing a market and partnering with booksellers, we will be too far behind the game. This will leave our marketplace wide open to someone from overseas to come in and exploit it – and we will lose control.”

Pan Macmillan’s digital marketing manager, Victoria Nash, and Allen & Unwin’s digital publishing director, Elizabeth Weiss, have much in common. Their companies are the only two Australian publishers actually producing e-titles, with Pan Macmillan offering online versions of 300 British and 308 Australian titles, and Allen & Unwin fielding more than 1200, most of them Australian and available on the Australian website eBooks.com. And both have looked on with envy at the sales generated by the customer-friendly Kindle system.

Weiss says there are also lessons to be learned from Sony’s launch in Britain late last year, in which the e-reader was introduced to old-fashioned book buyers in the familiar environment of the giant Waterstone’s book chain.

“All evidence indicates Australian readers are ready to use e-books on a larger scale than is currently the case,” she says. “It’s a matter of devices, availability, pricing and promotion.”

Richard Siegersma, executive chairman of Central Book Services, says that e-book reading needs to be made easier for Australians.

He won’t give sales figures for the various e-readers his company supplies, but says the electronic devices remain “an emerging market” because there are too few Australian titles available.

His company will soon set up its own e-book website, carrying 70,000 international titles, and will also launch a new, cheaper e-reader, the Eco-reader, costing less than $500 and linked to the website.

But will the inevitable boom in e-books mean the death of the paper book in Australia? Here, according to the most recent BookScan figures, 2008’s $1.214 billion book sales represented a 2 per cent increase on the previous year.

Sydney book seller Jon Page dismisses talk about the death of the book that he heard at last month’s New York book fair. At best, he says, e-books are predicted to eventually take up about 10 per cent of the book market, but with many sales concentrated in business, instructional and educational books.

Mandy Brett is also confident of the future of old-fashioned “hard” books. “People who love books and reading are very attached to the experience of paper.”

But e-books offer people an alternative experience, with e-readers allowing them to take 20 (or 40) books on holiday. Don Grover, chief executive of the Dymocks Group, says that his e-book website sales exceeded his two-year projections in its first six months, with current sales topping 2000 a month.

He sees digital book sales enhancing hard-book sales, with e-book formats allowing bookstores to hold up to 2 million titles and do “print on demand” versions of any book. He is also excited about new software from local company DNAML, which will allow film and video footage to be embedded in a e-book.

“Imagine: you’ll be able to watch an author explaining to you what a book is about,” he says.

Grover says reports of the death of the book are made by “people with no understanding of the consumer”. “Our research is clear: readers still want the smell and touch of a book.”

In his view, people who fuss about special e-readers also miss the point that many people read e-books on laptops.

Sherman Young, acting head of the department of media, music and cultural studies at Macquarie University and author of The Book Is Dead (Long Live the Book), says that this year the e-book has finally begun to move out of “geek territory” and into acceptance as an inevitable publishing development.

But the academic believes that the e-book will not kill the paper book until the experience of reading one is better, cheaper and more convenient. “An entire electronic book ecosystem needs to evolve – involving publishers, retailers and readers,” he says. So far, he says, Amazon’s Kindle store is an early version of that ecosystem, but still confined to the US.

“It will happen in my lifetime,” predicts the 43-year-old, who has the new Sebastian Faulks-penned James Bond novel on his iPhone.

“The paper book will eventually die. Or there will be a repurposing of it. The analogy I like to use is digital photography. Overnight – it took 10 years – nobody has a film camera any more and most people browse their photos on computer. But people still print some photos – and they still get photo albums.

“With books, a similar thing will happen, with most reading done on some sort of electronic device. Then people will turn to print for really nice photo books or gifts.”

Late last week California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger called for publishers to replace textbooks with their electronic equivalent. Publishers Weekly posted this article about the book industry’s response to his plea:

Pearson Answers Schwarzenegger’s Call for E-Textbooks

By Craig Morgan Teicher — Publishers Weekly, 6/18/2009 7:46:00 AM

Last week, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger proposed replacing school textbooks with e-books in order to help plug a state budget gap. Now, textbook giant Pearson has responded with digital content to supplement California’s programs in biology, chemistry, algebra 2, and geometry.

In a statement made recently, Schwarzenegger said, “Kids are feeling as comfortable with their electronic devices as I was with my pencils and crayons. So why are California’s school students still forced to lug around antiquated, heavy, expensive textbooks?” But easing the strain on students’ backs was not the Governor’s main reason for putting out a call to developers to create electronic textbooks. The current budget gap in the state is estimated at $28 billion.

Peter Cohen, Pearson’s CEO of North America school curriculum business, said, “We believe it is important to take these forward steps toward an online delivery system and we are supporting the Governor’s initiative, recognizing there are numerous challenges ahead for the education community to work through,” including “how we ensure that low income and disadvantaged students receive equal access to technology; how we address the needs of English language learners; and how we protect the intellectual property rights of content and technology creators to support future investment and innovation.”

According to the official Web site for California’s Free Digital Textbook Initiative, e-books must “approach or equal a full course of study and must be downloadable.” The site also offers instructions and links for publishers of e-books to submit books for consideration for use in California schools.

Pearson is the first major company to respond to Schwarzenegger’s initiative, which garnered an array of responses from the media, from speculation in the U.K. that others will imitate the project, to others who point out that e-books in school are not more environmentally friendly than print textbooks.

This all provides ideas for thought and discussion for schools and libraries now and into the future.

The teaching of handwriting and is there a future in it?

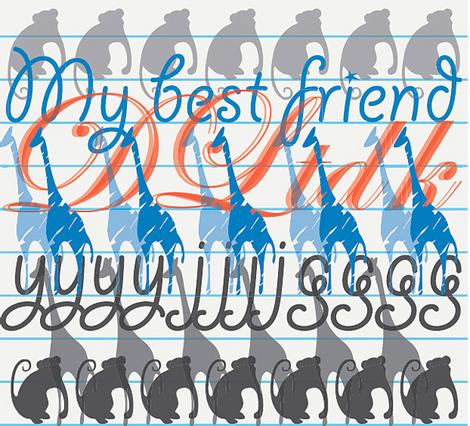

Saturday’s Age published a very interesting and thoughtful article by Suzy Freeman-Greene entitled The Write Stuff on the subject of teaching handwriting.

She has some very interesting thoughts such as

Florey, an American author, believes handwriting is in crisis. It’s often illegible, she told ABC radio, and in some US schools, kids are being taught something known as “keyboarding”. Studies have shown that kids master reading more easily when they write some of the words at the same time. There is, she says, a direct connection from brain to hand. But beyond fourth or fifth grade, US schools pay little attention to the quality of handwriting.

After hearing Florey, I’m mighty glad that Victorian prep students are straining over their giraffes and monkeys (though I’m not sure what they’re doing at secondary schools). But you have to wonder what this penmanship will be used for, other than filling out forms and signing credit-card receipts. Will the next generation write in diaries? (Who needs to when you can record every moment on the web?) If they no longer send love letters, will they save those heartfelt emails and flirty texts for posterity?

Handwriting began as a specialised enterprise. (Think of those medieval monks bent over illuminated manuscripts.) And maybe it will again become a rarefied activity, closer to calligraphy than a daily necessity. Today, a handwritten letter already has a rare, intimate quality.

When you pause to think about what we actually do use handwriting for today it is a sobering thought that it may well become a lost art.