Once upon a digital time

Christina Bell, of Mitcham’s Central Book Services, browses her e-reader over coffee.

Photo: Pat Scala

Liz Porter

June 21, 2009

MOST evenings Mandy Brett curls up on her couch to read a new Australian novel on her Sony e-reader, an electronic device that stores up to 350 books and allows her to “turn the page” with a flick of her finger. The senior editor at local company Text Publishing, Brett, 46, switched to e-reading 18 months ago because lugging manuscripts home was giving her a sore back.

A self-described “gadget head”, she is already onto her second e-reader, having recently upgraded to a newer version of the device. If she’s stuck waiting for a friend in a cafe, she’ll whip out her iPhone and read a few pages of Let the Right One In, a novel by Swedish writer John Ajvide Lindqvist.

For Brett, the e-reader means work. When she reads for fun, she sticks to paper books. The current embryonic state of Australian e-publishing makes it easy for her to keep her dual reading lives separate. As yet, she says, there are still too few local e-books available for download. While all major Australian publishers, including Text, are preparing for digitalisation, the only locals already selling e-versions of their titles are Pan Macmillan and Allen & Unwin. The only book chain marketing them is Dymocks. And the only bookshops where would-be customers can inspect an e-reader are Dymocks’ main Sydney store and Melbourne’s Reader’s Feast.

If Brett were in the US, she could have a $US359 Kindle – a wireless e-reader launched by Amazon.com in late 2007. Without going near a computer, she could use her device to download any one of many thousands of Amazon.com titles – and pay only $9.99 for the privilege. And she would be one of a growing mainstream crowd doing so. For every 100 “hard” book copies ordered on Amazon, an additional 35 Kindle editions are now being sold.

For more than 10 years, the e-book has been hyped as the “next big thing” in world publishing – a prediction usually underpinned by dire prophecies about the imminent death of the conventional “hard” book.

Now, more than a decade since the launch of the first clunky, chunky, expensive e-readers (one of which lost its stored information when the batteries were changed), the e-book era seems finally to have dawned, at least in the US.

E-publishing was the hot conversation topic among the 1500 publishers and booksellers gathered at last month’s BookExpo America in New York. American publishing association figures for the first quarter of 2009 had just revealed that e-book sales comprised 1.6 per cent of US publishing sales – a formidable increase, given the fact that, pre-Kindle, they were languishing at about 0.2 per cent. Moreover, e-books were the only book industry sector showing any kind of sales surge amid the global financial crisis, rising 131 per cent during that period.

Sydney bookseller Jon Page was at the BookExpo and says the buzz about e-books was real, offering proof that “the reality (of e-publishing ) was starting to outpace the hype”.

But when will the e-book revolution hit Australia? For many individuals, it is already here.

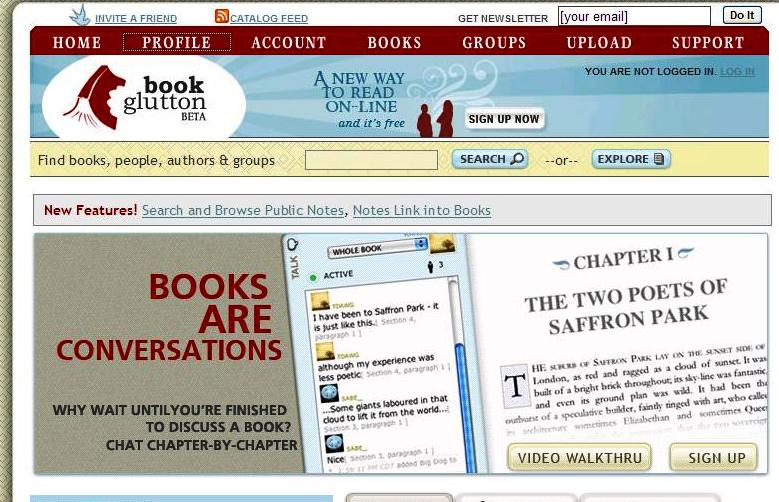

Melburnian Christine Bell is working in the midst of it. The manager of the technical helpdesk at Mitcham’s Central Book Services, which supplies the readers that Dymocks and Reader’s Feast sell, she says there are two groups of e-reader buyers. Twentysomething students love them. And so do 50-somethings, who have the time to read and explore the new world of digital reading – and the money to buy one of the five different e-readers that her company supplies, at prices ranging from $569 to $1600.

Herself a keen e-book reader, Bell owns a $569 Hanlin V3, containing free out-of-copyright classics from Gutenberg.com, along with Matthew Reilly’s Seven Ancient Wonders, which she bought from the Dymocks-Pan Macmillan site. A regular on the internet e-book forum mobileread.com, she also organised a meeting of 14 e-book buffs in a CBD cafe last weekend. All brought their different e-readers, including one Kindle.

“One woman came from Sydney for it,” she says.

The e-book revolution has also arrived for 40-something Melbourne communications manager Lisa Bigelow, who was thrilled to find that her iPhone came with the Stanza book-reading application. She promptly bought a program containing 40 classic novels, including Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities.“It’s something you can read when you are waiting somewhere,” she says. “It saves carrying a book around.”

Meanwhile, the e-reading revolution has been slowly emptying the bookcase of Sydney-based accountant Charlie Perry, 31, who bought his Sony PRS-505 e-reader (the version before Mandy Brett’s PRS-700) for $450 on eBay in January last year. “That’s about half the price of buying an iRex iLiad (the e-reader Dymocks launched in December 2007),” says Perry, who happily uses his e-reader on the bus.

“I am a big reader – and I like gadgets. The e-reader weighs about 300 grams – about the same as a hardback book.” But he still reads paper books because, as with all Australian e-book fans, he is stymied by the comparative unavailability of Australian e-titles. He is also thwarted by the fact that many overseas book sites “lock out” buyers with Australian credit cards because they only have the rights to sell books in their particular territories. E-book fans, he says, share tips on “fooling” overseas sites into selling to them (by giving a US address for example), while gift vouchers allow Australians access to US sites.

His 18 months of e-reader ownership have transformed Perry’s attitude to book ownership – prompting him to give “hard” books away once he has read them.

“I’m determined this year to get my backlog of unread books down to zero, clear my bookshelf completely and move entirely over to digital reading. You come to value the experience of reading far more than you value the object. This, I suspect, is going to become a major issue for booksellers. The cost of reading a book must be cheaper than the cost of owning it – and significantly so.”

When publishers and booksellers speak of the arrival of the e-book revolution, they mean a visible, measurable and profit-making phenomenon. That phase, they agree, will probably begin in the next year or so, and will be kicked along by the launch in Australia of the Sony e-reader, expected in the next 12 months.

But opinions vary on the preconditions necessary to kick off a local e-book boom.

HarperCollins marketing director Jim Demetriou says his company has plans to offer every new title in e-book format, expanding its range to 1000 over time. But he believes e-books will only hit the mainstream when Australians get something like a Kindle. The launch of the Sony PRS-500 was the first breakthrough, he says.

“Before that, people were reading books on Palm Pilots. When Sony launched, sales doubled. But what drove sales in the US was the Kindle,” he says. “It quadrupled sales overnight.”

Others, such as Text’s Mandy Brett, or Australian Booksellers Association CEO Malcolm Neil, say lack of a sufficient breadth of “content” is the problem.

“Forget the Kindle and the Sony reader,” says Neil. “We can get hold of those. We can’t get hold of the books.”

E-publishing will remain “a world trend still waiting to happen in Australia” until all publishers, not just Pan Macmillan and Allen & Unwin, make their titles available in e-book form. According to Neil, Australian booksellers are watching overseas e-publishing growth with increasing frustration. Not because they are worried about competition with e-books, but because they want to be part of the e-publishing action.

“Our biggest concern is that if publishers hold off too long on developing a market and partnering with booksellers, we will be too far behind the game. This will leave our marketplace wide open to someone from overseas to come in and exploit it – and we will lose control.”

Pan Macmillan’s digital marketing manager, Victoria Nash, and Allen & Unwin’s digital publishing director, Elizabeth Weiss, have much in common. Their companies are the only two Australian publishers actually producing e-titles, with Pan Macmillan offering online versions of 300 British and 308 Australian titles, and Allen & Unwin fielding more than 1200, most of them Australian and available on the Australian website eBooks.com. And both have looked on with envy at the sales generated by the customer-friendly Kindle system.

Weiss says there are also lessons to be learned from Sony’s launch in Britain late last year, in which the e-reader was introduced to old-fashioned book buyers in the familiar environment of the giant Waterstone’s book chain.

“All evidence indicates Australian readers are ready to use e-books on a larger scale than is currently the case,” she says. “It’s a matter of devices, availability, pricing and promotion.”

Richard Siegersma, executive chairman of Central Book Services, says that e-book reading needs to be made easier for Australians.

He won’t give sales figures for the various e-readers his company supplies, but says the electronic devices remain “an emerging market” because there are too few Australian titles available.

His company will soon set up its own e-book website, carrying 70,000 international titles, and will also launch a new, cheaper e-reader, the Eco-reader, costing less than $500 and linked to the website.

But will the inevitable boom in e-books mean the death of the paper book in Australia? Here, according to the most recent BookScan figures, 2008’s $1.214 billion book sales represented a 2 per cent increase on the previous year.

Sydney book seller Jon Page dismisses talk about the death of the book that he heard at last month’s New York book fair. At best, he says, e-books are predicted to eventually take up about 10 per cent of the book market, but with many sales concentrated in business, instructional and educational books.

Mandy Brett is also confident of the future of old-fashioned “hard” books. “People who love books and reading are very attached to the experience of paper.”

But e-books offer people an alternative experience, with e-readers allowing them to take 20 (or 40) books on holiday. Don Grover, chief executive of the Dymocks Group, says that his e-book website sales exceeded his two-year projections in its first six months, with current sales topping 2000 a month.

He sees digital book sales enhancing hard-book sales, with e-book formats allowing bookstores to hold up to 2 million titles and do “print on demand” versions of any book. He is also excited about new software from local company DNAML, which will allow film and video footage to be embedded in a e-book.

“Imagine: you’ll be able to watch an author explaining to you what a book is about,” he says.

Grover says reports of the death of the book are made by “people with no understanding of the consumer”. “Our research is clear: readers still want the smell and touch of a book.”

In his view, people who fuss about special e-readers also miss the point that many people read e-books on laptops.

Sherman Young, acting head of the department of media, music and cultural studies at Macquarie University and author of The Book Is Dead (Long Live the Book), says that this year the e-book has finally begun to move out of “geek territory” and into acceptance as an inevitable publishing development.

But the academic believes that the e-book will not kill the paper book until the experience of reading one is better, cheaper and more convenient. “An entire electronic book ecosystem needs to evolve – involving publishers, retailers and readers,” he says. So far, he says, Amazon’s Kindle store is an early version of that ecosystem, but still confined to the US.

“It will happen in my lifetime,” predicts the 43-year-old, who has the new Sebastian Faulks-penned James Bond novel on his iPhone.

“The paper book will eventually die. Or there will be a repurposing of it. The analogy I like to use is digital photography. Overnight – it took 10 years – nobody has a film camera any more and most people browse their photos on computer. But people still print some photos – and they still get photo albums.

“With books, a similar thing will happen, with most reading done on some sort of electronic device. Then people will turn to print for really nice photo books or gifts.”

Late last week California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger called for publishers to replace textbooks with their electronic equivalent. Publishers Weekly posted this article about the book industry’s response to his plea:

This all provides ideas for thought and discussion for schools and libraries now and into the future.